This week’s post is a bit of an unusual one. Some friends of mine mentioned in conversation that they want to create a Web-based digital card game. As it happens, I have a half-baked card came design lying around from a few years ago, because of course that’s something I tried at some point, because why not. I mentioned it to them, and they requested I write it up so they could evaluate it for their project.

So, by special request, this week’s post is a slightly rambling overview of a half-finished card game design from two years ago. I have no idea if this’ll end up being used — I’d never designed a card game before, and maybe five people have played this one to give their opinion, so it comes only lightly recommended — but, for their consideration and your interest/amusement, here is the first public write-up of my concept for Maraud.

Inspiration

Maraud is equally inspired by Games Workshop’s table-top strategy games and Gwent, a card game created for and featured in the video game The Witcher 3. From table-top games come several battle systems and a smattering of other mechanics intended to emulate, in a simplified way, the challenges of commanding a pre-modern battlefield. From Gwent, however, comes the larger vision for the game.

Gwent‘s role in The Witcher 3 is not only as a mini-game players can use to pass the time. In the setting of the larger game, it has a social role that I found fascinating. Gwent is so popular in the world of The Witcher 3 that almost every character seems to play it, and a very common conversation pattern in the game is to meet a new character for the first time, explore some other dialogue options, then propose and immediately sit down to a game of Gwent. That social ritual — meeting a complete stranger in person and, within minutes, being able to sit down to a friendly and mutually-familiar game — seemed so foreign and interesting to me that I wondered if it would be possible — not achievable, but merely possible — in the real world.

I thought about what kind of game could be played in such a way. I wanted it to be tactical and deck-based as I was still interested in the battlefield theme. However, in order for the game to be accessible, it needed to be easy to play. Gwent can require a lot of arithmetic that might be uncomfortable or tedious for many players; and Magic: the Gathering, the game that established this entire genre of card games, often requires so many modifiers, tallies, tokens, etc. that players must bring along a small kit of dice and markers in order to keep track of what was going on. Please don’t mistake me: these complexities aren’t bad traits, and they allow for a lot of interesting opportunities in their respective games. But they also make those more difficult to learn and more difficult to play. I wanted to capture a similar feeling and challenge, but in as accessible a package as possible.

From these considerations I derived the constraints that I designed my game around. I wanted it to be possible to play the game with cards only, without any requirement for additional markers or tallies. I wanted whatever arithmetic the game required to be as simple as possible such that even those with only a modest comfort with mental math wouldn’t feel the need for scratch paper. I wanted the game to be “pause-able”: players who had left the table and forgotten what was happening should be able to return and deduce the state of the game from only what was on the table without reference to purely-remembered information.

And of course, alongside everything else, it still had to be fun.

The Cards

Like the games that inspired it, the theme for Maraud is pre-modern (medieval, classical, ancient, etc.) land warfare. At a very high level, a game of Maraud represents a skirmish or pitched battle between the forces commanded by the game’s two players. These forces are represented by the cards, with each card representing a unit of soldiery — spearmen, cavalry, archers, etc. — that might classically have been maneuvered as a single formation.

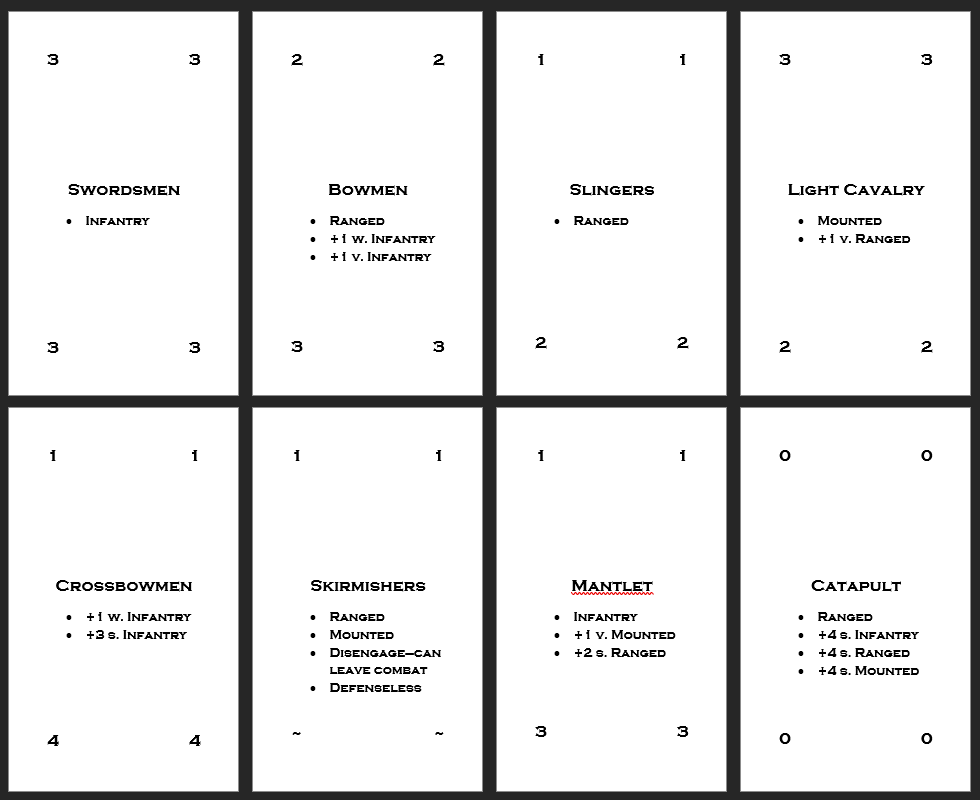

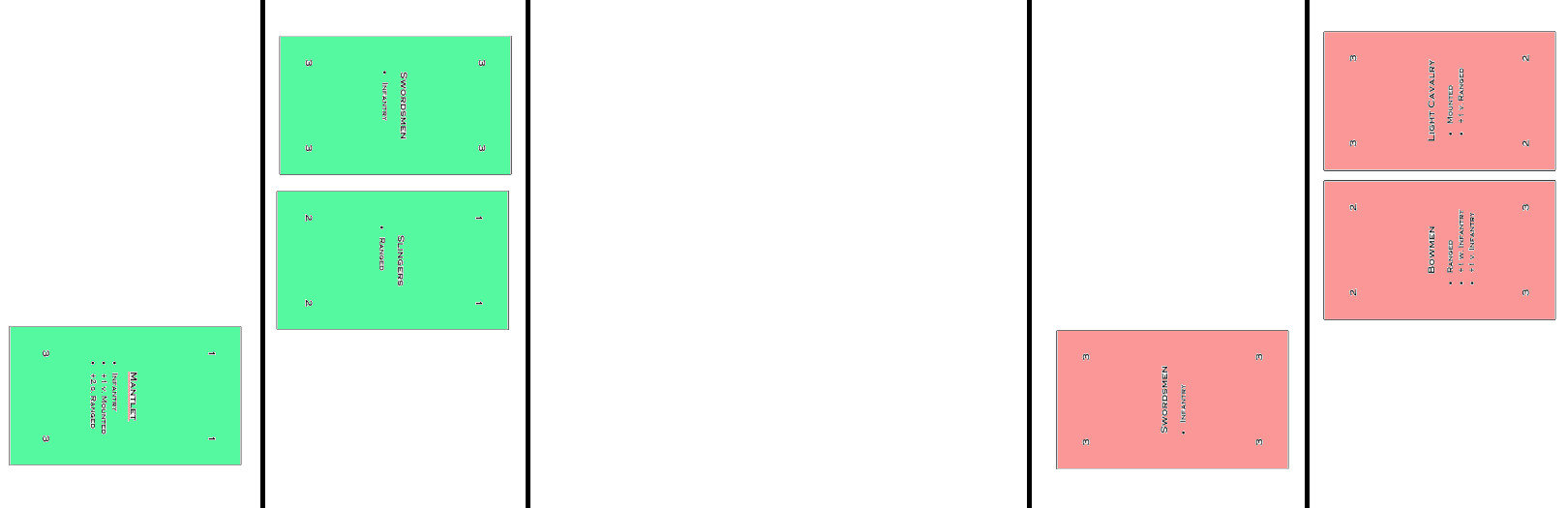

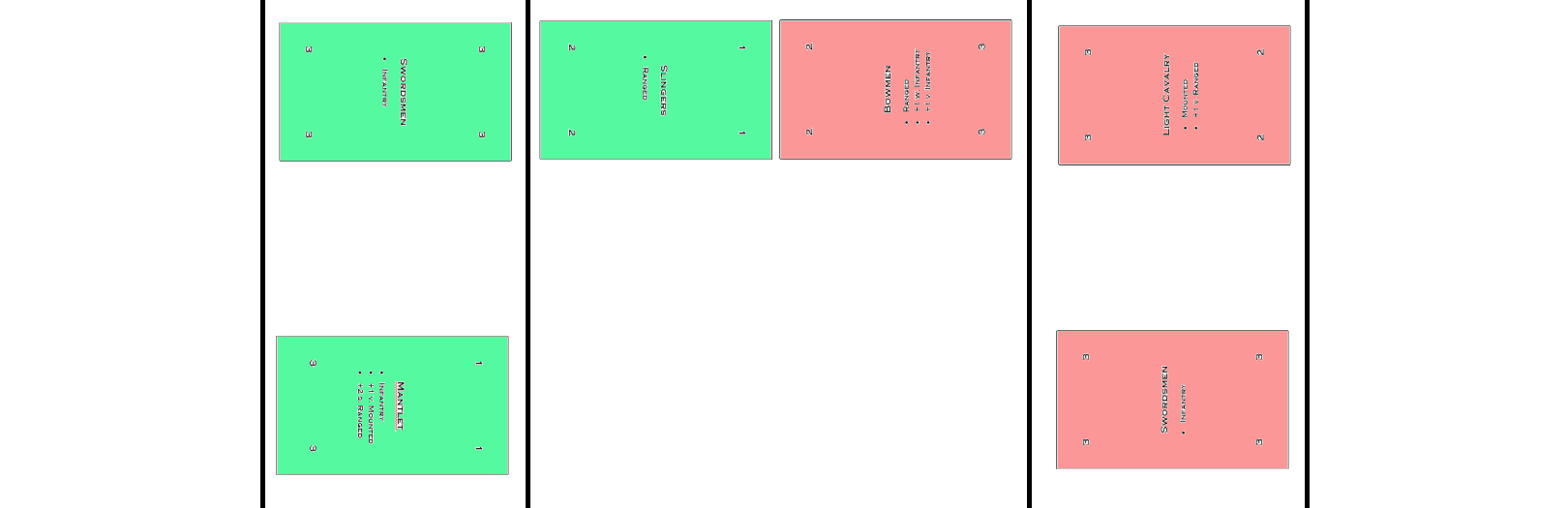

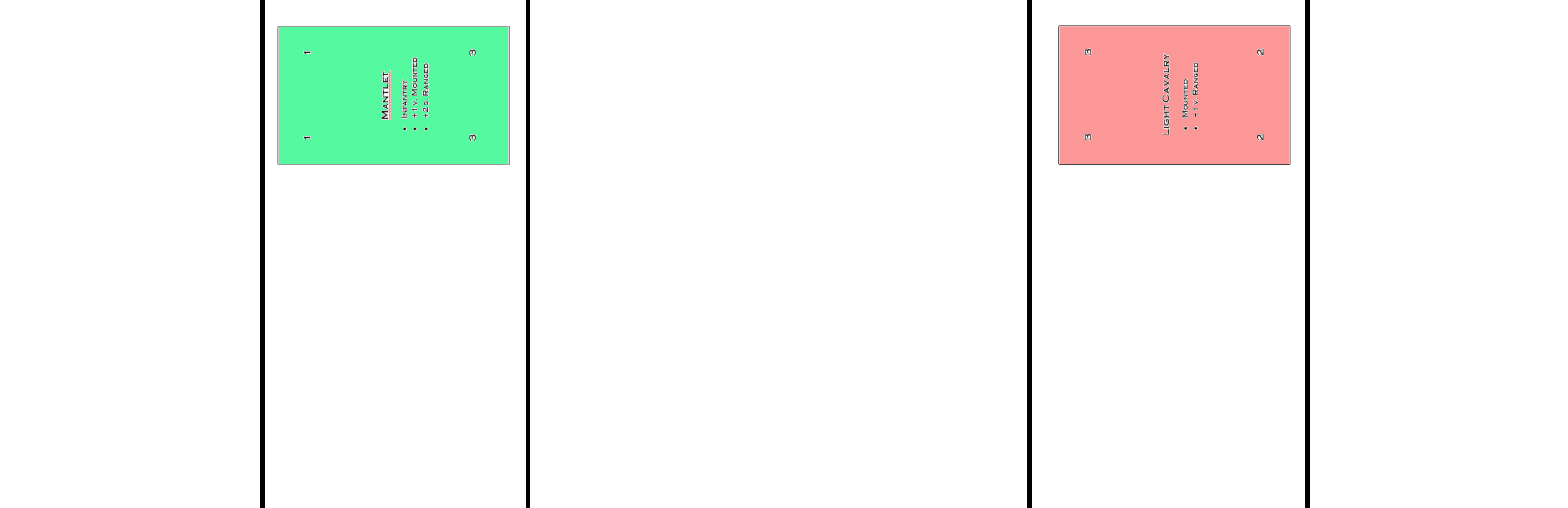

Every Maraud card shows five different kinds of information: name, classes, offensive strength, defensive strength, and bonuses.

- Names are almost but not entirely cosmetic. The name of a card doesn’t typically affect anything but theme and immersion; however, it is theoretically possible for cards to have bonuses that operate on other cards specified by name.

- Classes are keywords used to describe what kind of unit a card represents. For example, a Swordsmen card’s class is Infantry, while Skirmishers are both Ranged and Mounted. The class(es) of a card determine which modifiers affect them and which bonuses are activated in their presence.

- Offensive strength is a number that represents the combat prowess of a unit when in an offensive formation. Formations will be discussed in more detail momentarily.

- Defensive strength is the counterpart to offensive strength, representing a unit’s prowess when in a defensive formation.

- Bonuses are conditional modifiers applied to cards under conditions specified on the card. Bonuses are typically used to represent combat specializations and vulnerabilities. For example, to represent that archers are particularly vulnerable to fast mounted strikes, Light Cavalry receive a +1 strength bonus when fighting against Ranged cards.

The concept of formations, mentioned above, is fundamental to Maraud’s use of cards. Formations are essentially “modes” in which cards can be placed that change their behavior in the game. Notice how the cards in the image above all have two pairs of numbers, one pair at the top of the card and one pair at the bottom. (Except for the Skirmishers. Ignore them for now, though; they’re weird.) Those are the offensive and defensive strengths, respectively, and they represent how well those soldiers fight depending on how they’re “formed up.” (Recall that every card represents a unit of soldiery.) Cards can only be in one formation at a time, and it requires a turn (discussed later) to change a card’s formation. The card’s current formation is represented by it’s orientation on the game table: if it’s right-side up relative to the player who played it, then it’s in offensive formation; but if it’s upside-down, it’s in defensive formation. This idea of formations, along with the “clash” combat system, form the basis for all the rest of Maraud’s mechanics.

The Clash Combat System

Cards represent units of warriors, so to represent combat between those units, Maraud allows cards to “clash.” A clash is simply an engagement between groups of opposing cards; it represents the place on the battlefield where opposing warriors have come together in active combat (as opposed to maneuver). The only way to eliminate an enemy’s card’s is to engage and fight them in clashes.

The easiest way to describe the mechanics of clashing is to talk about the turn system. During a hand (discussed later), Maraud is played by turns, and the rule governing actions during turns is simple: you can only do one thing. You can play a card, taking it from your hand and placing it face-up on the table in front of you in a formation of your choosing. You can change the formation of a card that you’ve already played, so long as that card isn’t engaged in a clash. If a card is in offensive formation and isn’t already in a clash, you can direct that card to attack one of your opponent’s cards to initiate a new clash, or you can have it join one that’s already in progress. You can also choose to resolve a clash (discussed momentarily). Whatever you choose to do, though, that action will consume your turn, because you can only do one thing per turn.

I emphasize this rule because, as simple as it seems, it is the most important factor when choosing what to do. Every action costs time, and timing is everything in Maraud. You can play a card, thereby bringing out new forces that you can use to target your enemy’s cards. However, playing that card will consume your turn, so your opponent will have the chance to react — perhaps with a preemptive strike, or by moving the card you were planning to attack into another clash so that you can’t isolate it. Furthermore, because attacking and resolving are separate actions, your opponents will always have the chance to add more of their cards to a clash, eroding or potentially reversing your advantage. Doing so, however, will consume their turns and hand the momentum, and the chance to counterattack, back to you.

Adding nuance to this system are the bonuses, which typically take the form of combat strength boosts activated by the presence of other specified cards in a clash. At present, there are three bonus activation conditions: versus bonuses (v), which activate when specified cards appear among the opposing cards in a clash; with bonuses (w), which activate when specified cards appear among the allied cards in a clash; and supporting bonuses (s), which activate when a certain class appears among allied cards and both cards — the ally and the recipient of the bonus — are in offensive formation.

These three systems — formations, bonuses, and clashes — all really come together when resolving a clash. Once a card is in a clash, it’s “locked in combat” and can’t do anything else until the clash is resolved. (Normally, anyway; some cards, like Skirmishers, are unusual.) Resolving a clash is an action that consumes a turn; for resolution to occur, a player (either) must designate that he or she wishes to use a turn to do so. When that happens, both players sum up the total combat strength of all their cards in the clash. Only the combat strengths of active formations and bonuses are counted. The player with the highest total combat strength wins the clash, and all of the cards from the losing side of the clash are discarded. (In case of a tie, both sides discard all cards.)

The winner, however, must also discard cards; the total strength of the required discard is determined by calculating the strength of the default discard. To calculate this, simply sort the victor’s cards from the clash in order of combat strength. As above, the combat strength of a card for this operation is considered to be its strength in this clash, so formations and bonuses are factored in here. Then, from weakest to strongest, begin summing up the combat strengths of the cards until the next addition would make the total strictly larger than the total combat strength of the player who lost the clash. The set of cards which have contributed to this sum is the default discard. Note that the victor does not have to adhere to the default discard; he or she can choose to throw away other cards (from the clash) instead, so long as the total strength of the discarded cards equals or exceeds the strength of the default discard.

With the clash’s victor decided and all required cards discarded, one final step remains: all the cards that survived the clash are put automatically into a defensive formation. When this is done, the clash is considered resolved.

A Hand of Maraud

As mentioned above, Maraud is played by hands, and within each hand play proceeds by turns. At this point, I think it might be most instructive (and interesting) to walk through a hypothetical hand of Maraud. Keep in mind that, for the purposes of demonstration, this hand is simplified and very small; it would be quite unusual to play an actual hand where each player started with only three cards.

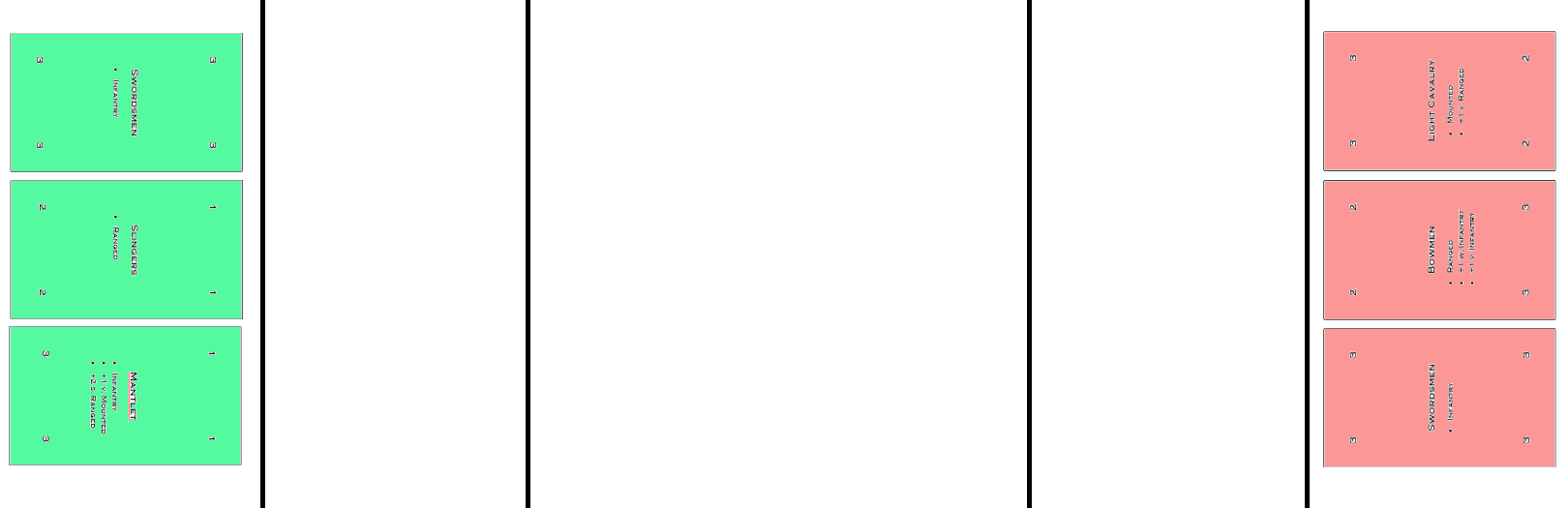

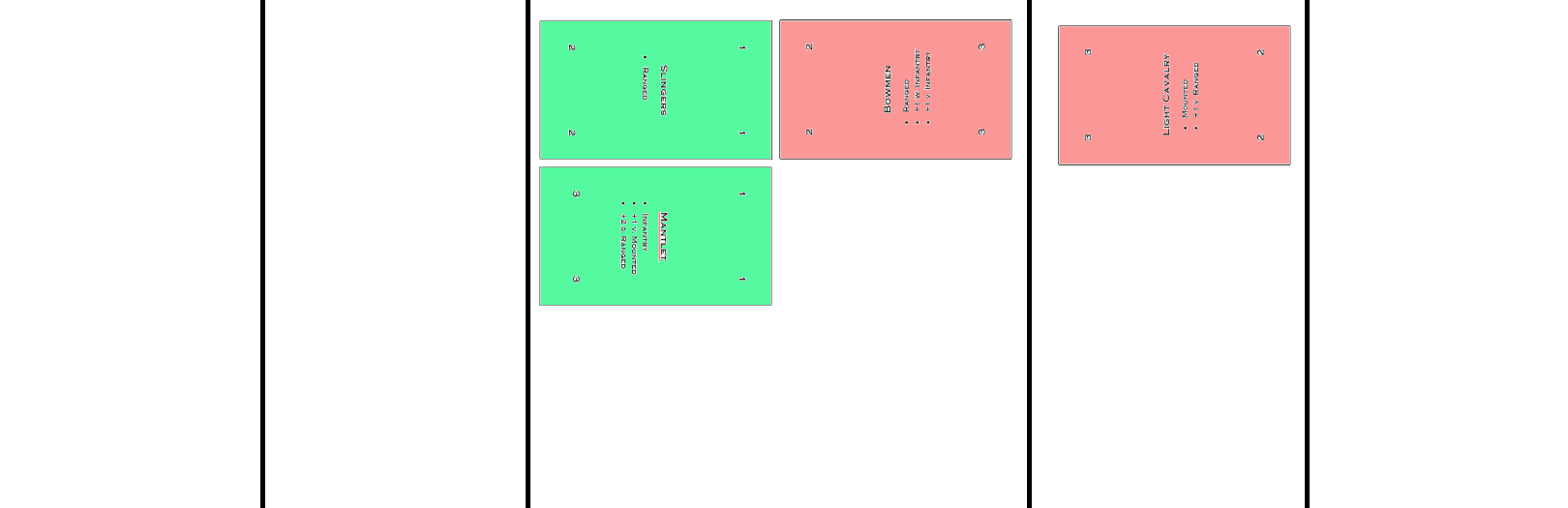

Turn 0: Start of Hand, Green Plays First

First, a note about the layout in these diagrams. I’ve divided the diagrams into five segments for the sake of clarity. The outermost segments represent the cards that are not yet on the table, players can’t opposing cards in these segments. The other three segments are all on the table: one segment for unengaged green cards, one for unengaged red cards, and one for clashes. I apologize if the images appear very small and the text difficult or impossible to read; these were the best diagrams I was able to create on relatively short notice.

Looking at the state of the game, it honestly doesn’t look good for Green. (Of course, Green doesn’t know that; she can’t see Red’s cards yet.) Red’s raw offensive strength beats green’s by 8 to 5, and it isn’t easy to find any clashes at all where Green would come out ahead. Green will have to be astute, and a little bit lucky, if she hopes to even neutralize Red’s advantage here.

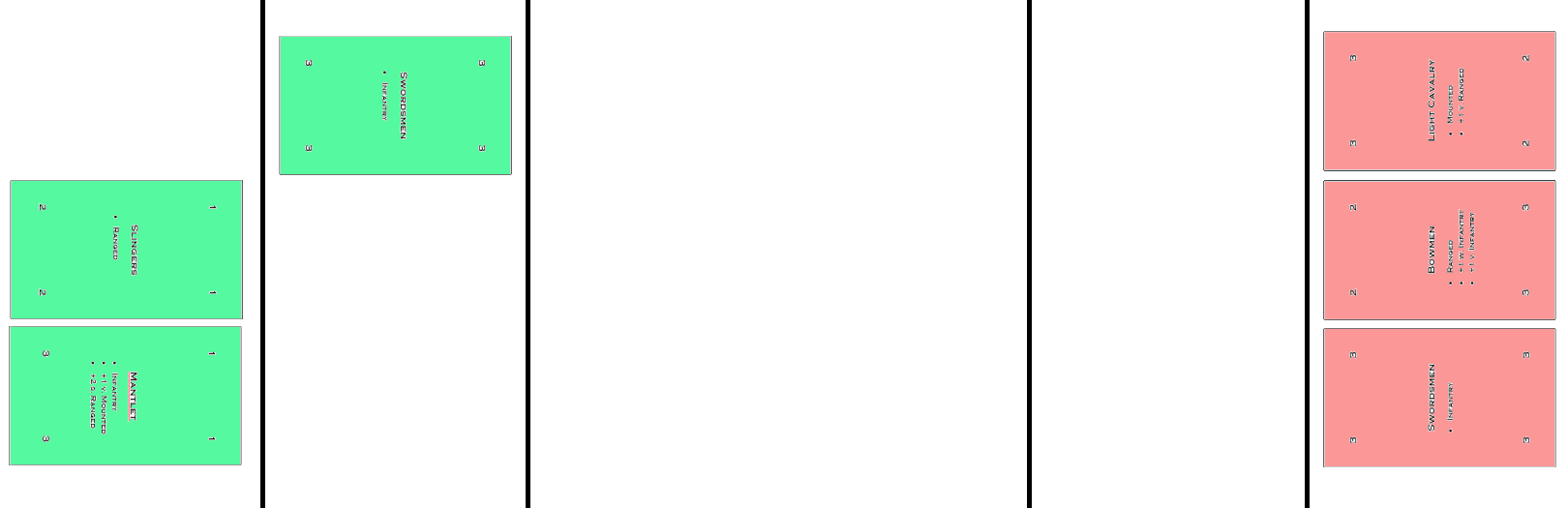

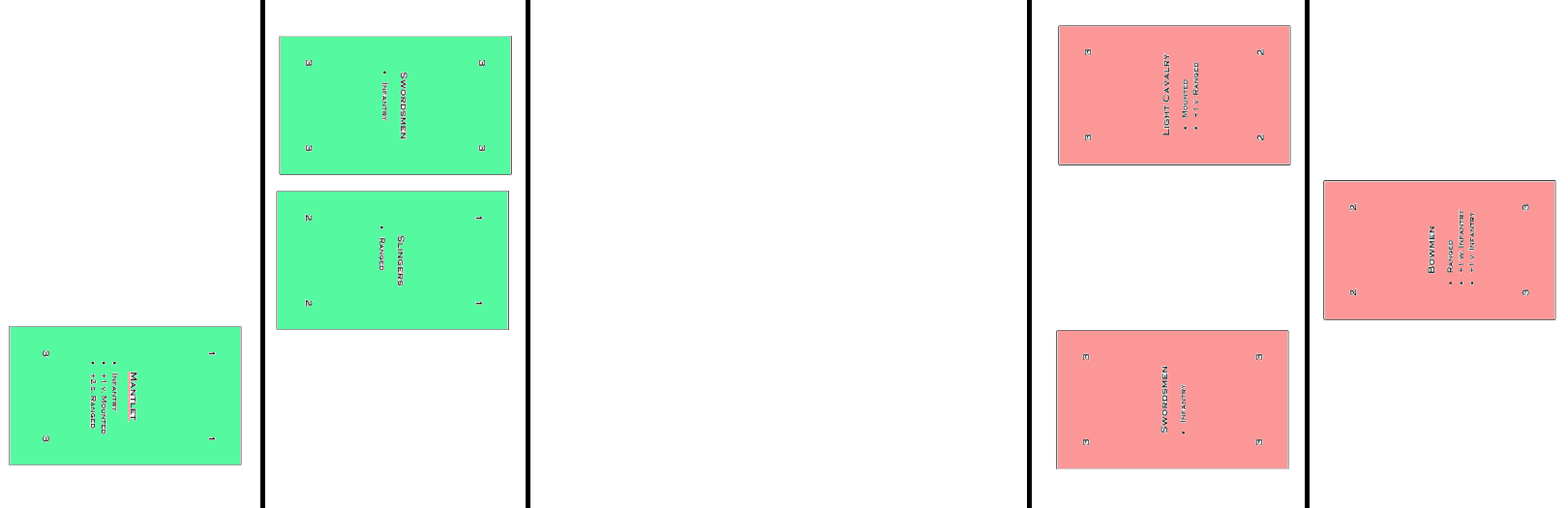

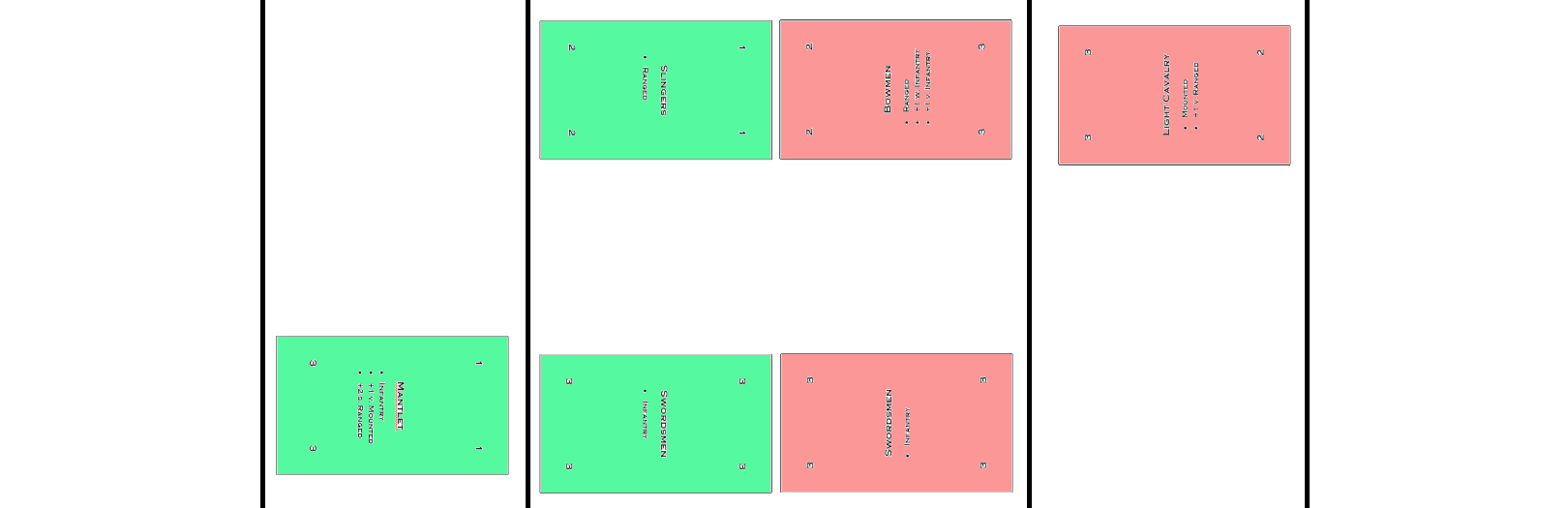

Turn 1: Green Plays Swordsmen to Table, Red Plays Next

These next few turns will mostly consist of players getting cards into play, so I won’t spend too much time commenting here. Important to note, however, is that (barring exceptions due to card-specific rules) you can’t play directly from your hand into a clash; so for a card to be useful in battle, it first must be “deployed” from your hand to the table.

Turn 2: Red Plays Swordsmen to Table, Green Plays Next

Red simply matches Green here. As far as anyone knows, nobody has the advantage at this point.

Turn 3: Green Plays Slingers to Table, Red Plays Next

Green brings out a very weak card, which is nevertheless strong enough that it could help the green swordsmen survive a clash against the red swordsmen. Fortunately for Red, that clash will never happen because he has other cards to play.

Turn 4: Red Plays Light Cavalry to Table, Green Plays Next

Light cavalry is a much better card than Green’s slinger, tipping the advantage strongly toward Red. One interesting thing to note about light cavalry is that, like most mounted cards and unlike most other cards, it’s stronger in an offensive formation than in a defensive one.

Turn 5: Green Plays Mantlet to Table, Red Plays Next

Green brings out a mantlet, which is a decent card, if a little tricky to use. If Red had no more cards, this might be a roughly even fight. Unfortunately for Green…

Turn 6: Red Plays Bowmen to Table, Green Plays Next

…Red has bowmen. With all the cards now literally on the table, the depth of Green’s disadvantage is plain for all to see. There are no clashes Green can initiate that will give her a direct advantage. She could burn a turn by switching one of her cards to a defensive formation; but since Red would have no incentive to attack that card, Green would just need to spend another turn later to bring it back, and by the look of things she may not have a lot of turns to spare. Instead, she decides to go on the attack and fish for a mistake from Red.

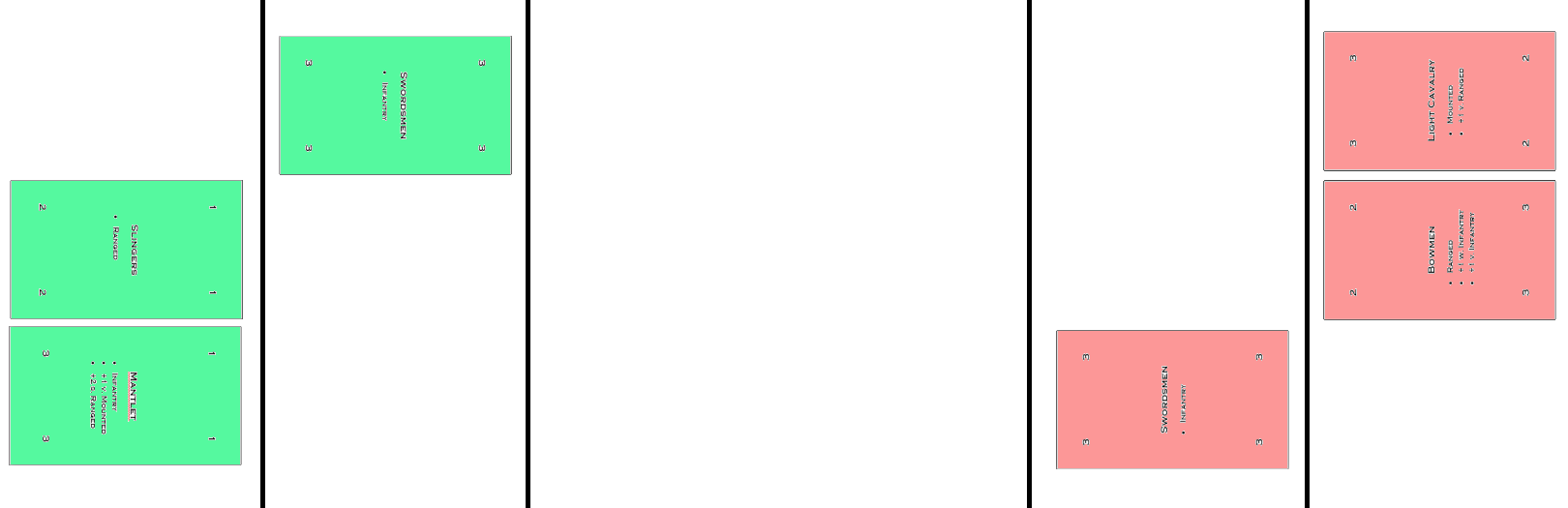

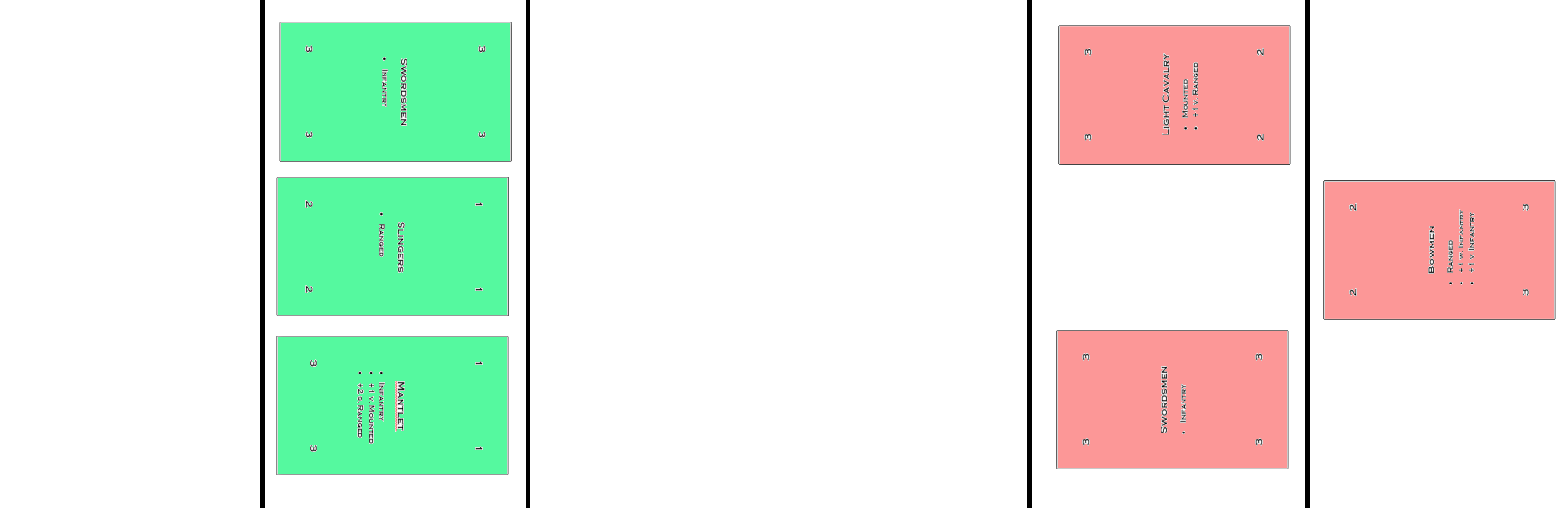

Turn 7: Clash #1, Green Slingers Versus Red Bowmen, Red Plays Next

Red now has quite a few options, none of which are really bad. Arguably Red’s best option would be to resolve Clash #1 immediately. This would destroy the green slingers and put the red bowmen into a defensive formation, which Green doesn’t have any individual cards strong enough to directly assail. However, there appears to be no real urgency to that, so Red decides instead to proactively neutralize Green’s strongest card.

Turn 8: Clash #2, Red Swordsmen Versus Green Swordsmen, Green Plays Next

As mentioned above, Red’s choice to neutralize the green swordsmen isn’t really a bad choice. However, it wasn’t the best because it leaves Green’s mantlet in a position to take advantage of the fairly robust bonus it gets from supporting allied ranged cards.

Turn 9: Green Mantlet Joins Clash #1, Red Plays Next

Green is now fully engaged and fighting very near to capacity. If Red were to properly bring his army’s strength to bear, he could guarantee himself a costly victory in this turn by sending his light cavalry to join Clash #1. Doing so would activate the green mantlet’s +1 bonus versus mounted cards, raising Green’s total strength in that clash from 4 to 5. However, the charging cavalry would bring 3 raw offensive strength and a +1 bonus of its own (activated by the presence of the green slingers), bringing Red’s strength in that fight to a total of 7. However, Red decides not to do that and focuses instead on hastening the elimination of Green’s swordsmen.

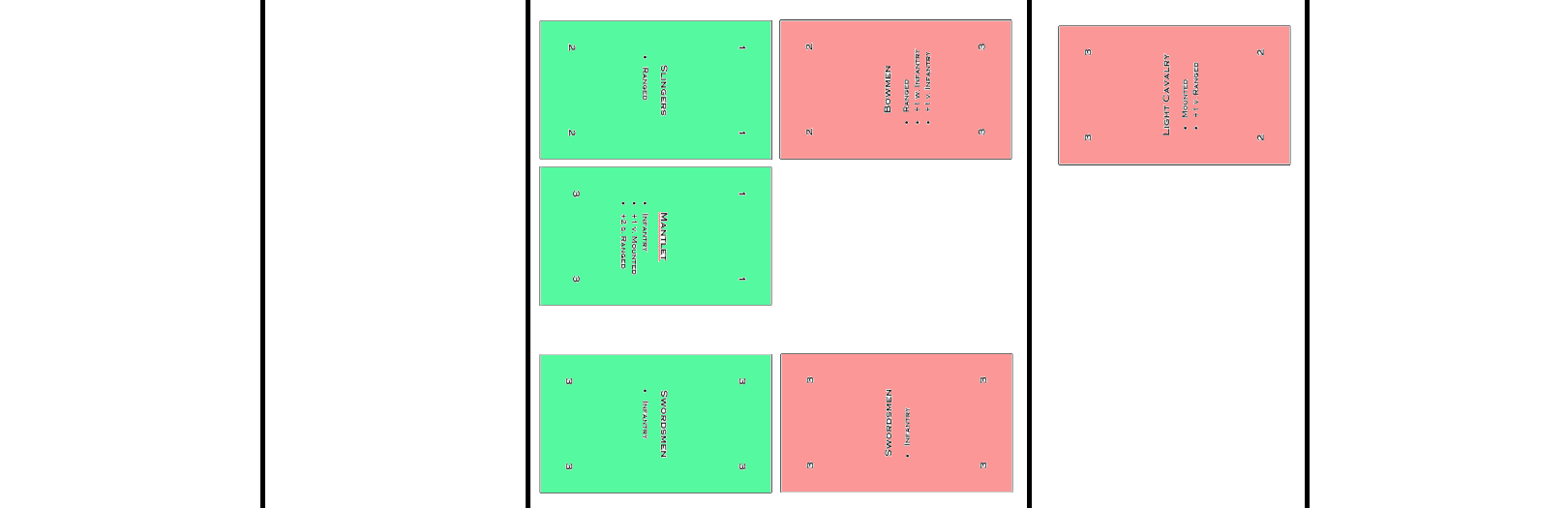

Turn 10: Red Resolves Clash #2, Green Plays Next

This is the Red mistake Green has been waiting for. If she resolves the final clash — which in fact she must do, as it’s her turn and there are no other moves she can make — then the fight will be between her mantlet and Red’s light cavalry, and the formations will be aligned just right…

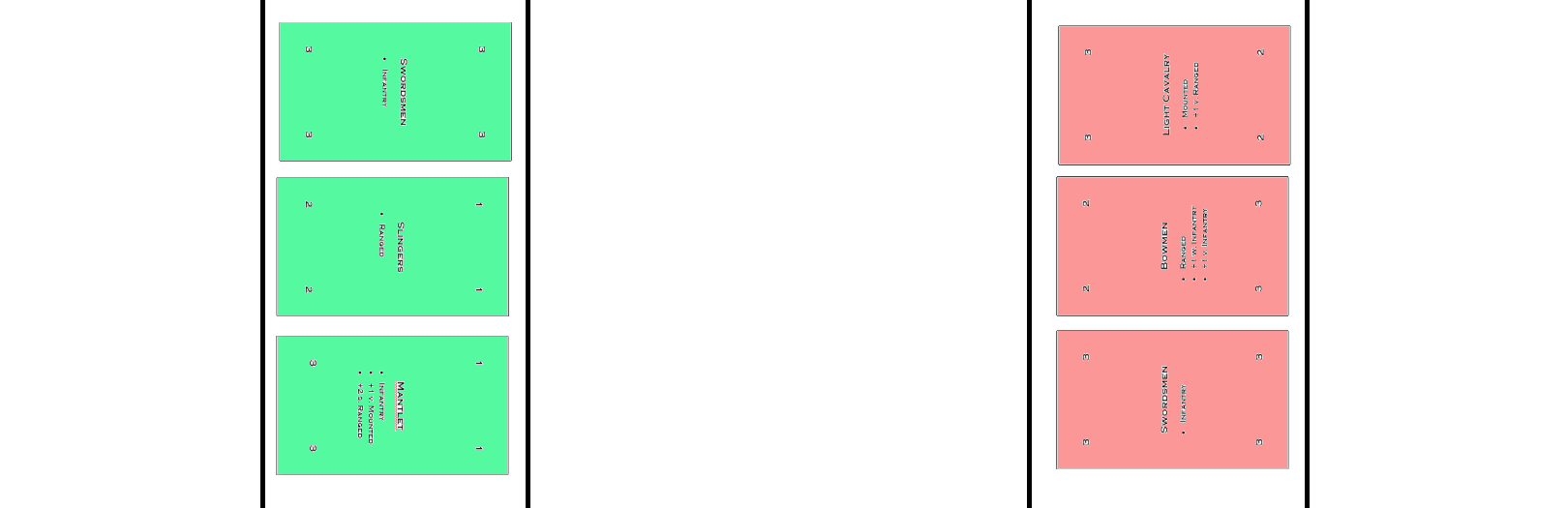

Turn 11: Green Resolves Clash #1, Forces Draw

It’s Red’s turn, but there isn’t anything he can do to salvage the situation now. His light cavalry is, broadly speaking, a stronger and better card than Green’s mantlet, but unfortunately for him she’s maneuvered such that he can only attack it while it’s is in a defensive formation, a clash the mantlet will win outright. His only option other than effective forfeit is to switch his cavalry to a defensive formation, which will prevent him from attacking next turn. If he does that, then Green’s only option on her turn will be to change the formation of her mantlet. The mantlet in offensive formation could tie a clash against the light cavalry in defensive formation; but before that clash can be initiated, Red will have switched his cavalry back to offensive formation, forcing the mantlet to either change its formation again or voluntarily lose. This is effectively a stalemate: both sides are locked in an endless cycle of formation switching. On the battlefield that Maraud is designed to represent, this is tantamount to two opposing forces parking themselves in equally defensible positions, refusing to move and simply glaring at each other until the sun sets and everybody goes home because it’s too dark to fight. This result, on both that battlefield and in Maraud, is considered a draw.

Of Conflicts Great and Small

As mentioned above, the hand we walked through in the prior section was very small. Most hands of Maraud that I’ve played involve five cards per side at least, with about six being the average. But that, of course, is a function of how the hands are created more than how they’re played. This is by far the least tested and most open-ended part of my design for Maraud. I’ve hardly play-tested these ideas at all, so please don’t think of the following as any sort of ordination regarding, “how it should be.” Instead, it’s a jumping-off point: here’s where I’ve taken the thinking so far, and where it goes next has yet to be discovered.

The original vision for Maraud was to represent larger conflicts by arrangements of multiple hands. In particular, I had a notion for representing a battle as a series of three flanks: left, right, and center. Likely the easiest way to describe this clearly is to simply walk through the phases.

Phase Zero: Decks

For a game of Maraud to be played, both players must have decks which represent their armies. There are many possible ways this could be done: all decks could be the same, standardized and balanced to make the game more constrained and predictable; there could be many different standard decks, each crafted by game designers to all play fairly, but a little differently; or players could be allowed to build their own decks as they are in Gwent or Magic: the Gathering. However it’s done, each player begins the game with their own deck of cards from which they will build their armies.

Phase One: Deployment

From the cards in their decks, players now deal themselves three hands, one for each of the flanks. Again, this could be done in many ways. The simplest and least strategic approach would be to simply shuffle the deck, divide it into three hands, and assign each hand to a flank at random without even looking at the cards in it. Another approach would be to conscientiously divide the cards into hands, then assign those hands conscientiously; this approach makes more sense with the addition of mechanics for espionage and terrain (described presently). A combined approach, which would features both randomness and tactics, might involve having decks of a certain preordained minimum size larger than the combined size of the three hands used in a battle, then shuffling that deck and dealing out a subset of cards; this subset can subsequently be manually divided into the flanks for the battlefield. Whatever variation is chosen, players should end the deployment phase with three small piles of cards, each of which is unambiguously assigned to a flank.

Phases Two: Espionage, Terrain, and Redeployment

So far, the only kinds of cards we’ve discussed have been military cards, each representing an individual unit of soldiery. In addition to these kinds of cards, the initial playable prototype included two other types: espionage cards and terrain cards. Though they aren’t deployed to a particular flank, espionage and terrain are added to a deck in the same way as military cards (see Phase Zero above). However, whereas military cards are intended to be used while playing a hand, espionage and terrain cards are used beforehand, specifically to add a layer of strategy to the deployment process.

There’s a sort of “rock, paper, scissors” principle underlying many of the military cards in Maraud. Spearmen fight well against cavalry, cavalry fight well against archers, archers fight well against infantry, and so on. This creates an incentive to seek out engagements that are favorable to you — not only in individual clashes while playing a hand, but at the flank level as well, if possible. Suppose you had one flank composed mainly of cavalry while another flank had comparatively many archers; also suppose your opponent has one flank composed almost entirely of spearmen. It would, of course, be to your advantage to have your archers engage your enemy’s spearmen while your cavalry busied themselves elsewhere. To do this, you need to have both some information about your opponent’s deployment and some ability to react to that information.

Espionage cards provide information about your opponent’s forces directly: they allow you to look at your opponent’s cards. A typical espionage card, when played during this phase of the game, will allow you to select one of your opponent’s flanks and reveal a small number of cards from that flank at random. Depending on what’s revealed and on what strategy your opponent has adopted, this may hint as to the general composition of that army. Deciding to what extent to trust that information is part of the game mechanic.

Contrastingly, terrain cards can only provide indirect information about your opponent’s forces, but they can also add modifiers that affect the game. Like espionage cards, terrain cards apply to the flanks — left, right, and center — but instead of revealing something about the opponent’s hand, they apply modifiers to the hand that will be fought on that flank. These modifiers typically function by neutralizing the bonuses of an entire class of cards; fog, for example, might prevent ranged cards from receiving any combat bonuses. In the original design, terrain cards were played by turns (as were espionage cards). Only one terrain card could be applied to a given flank at a time, and playing another terrain card on top of an existing one would cause both cards to be discarded. In this way, playing terrain can give players some indirect knowledge of their opponent’s deployment. If your opponent seems particularly eager to remove fog from a flank, it’s likely he has some archers there; but if he doesn’t mind the fog, you could take that as a sign that his archers are probably elsewhere.

The final mechanic involved in this phase is redeployment. After all espionage and terrain cards have been played, each player is given the chance to swap the flank assignment of two of their hands. They cannot change the composition of the hands; all hands must stay together as they were deployed in Phase One. However, the hand that was originally assigned to the left flank might switch assignments with the center flank, and so on. The order in which players redeploy matters, of course — watching your opponent redeploy could give a lot of information about how you want to redeploy — but to be honest, I haven’t explored this issue thoroughly yet.

In fact, there are quite a few issues with Phase Two that I’m not full happy with. In my very limited testing of this, spies in general turned out to be a lot less useful than I was expecting them to be. Terrain, by contrast, proved very useful, but there’s probably a more fun way to achieve that result than via the turn-by-turn mechanism I described above. I also considered making redeployment opportunities a playable card, allowing players more chances to position their flanks advantageously at the cost of being able to bring fewer of other cards (since all cards count toward the same deck size limitations). Lots of ideas, but unfortunately I haven’t explored them enough to know which, if any, are good.

Phase Three: Battle

The action at last! Once the deployment and redeployment are concluded, the battle itself is decided by playing to be the “best of three” on the flanks. In an order determined by the players (via a mechanism not yet deeply explored), each flank is played out as a hand of Maraud according to the rules described above. The only differences are the presence of terrain modifiers — which may or may not be present and affect the behavior of certain cards — and the ability to call up reserves.

In real war, reserves were units of soldiers intentionally kept out of the early fighting so that their freshness and mobility could be leveraged to deal with problems that arose throughout the battle. Maraud’s representation of this is a little different (though it could easily be modified to be more similar). In Maraud, any cards that have never been played — that are not on the table but are still in the hand of the player who owns them — are added to the army’s reserves. In later hands, players can then choose to discard one of the unplayed cards in their current hand in order to “bring up” a card of their choice from their reserves. Like every other action when playing a hand of Maraud, calling up a reserve card costs a turn.

The reserves mechanic serves a twofold purpose: (1) it allows the outcomes of earlier flank battles to have some limited but nontrivial influence on later battles, and (2) it adds risk to the strategy of under-supporting a single flank in order to over-support the other two. It also adds an incentive for players to win early flanks as efficiently as possible, or even to choose to lose early flank that isn’t going well in order to make the best cards from that flank available to other flanks as reserves. I still think there are some kinks to work out in the system; but on the whole, reserves are one of my favorite mechanics in the whole of Maraud.

Conclusion

This post has become far longer than I had ever anticipated. But before I finally bring it to a close, there are even more mechanics I want to discuss briefly, although I had even less chance to explore these than I had for some of the other mechanics mentioned above.

- Priority: Borrowing a term and concept from Maraud‘s Games Workshop inspirations, priority was my best and only attempt to address the problem of deciding who goes first. Throughout a battle, one or the other player will, “have priority”; who has priority for the battle is decided at the beginning of Phase Two (by agreement, convention, or just the flip of a coin). The player with priority plays the first espionage/terrain card in Phase Two and also redeploys first. The player with priority then chooses which of the three flanks will be played first; in that hand, this player will have the first turn. The player without priority then chooses which of the remaining flanks will be played next. When playing the hands for both the second and the third flanks, the player without priority will get the first turn.

- Lieutenants: Lieutenants are military cards with special behaviors and a lot of open-ended opportunities for unique abilities. For example, my playable prototype included one lieutenant called the “Martyr” who could, when on the battlefield and not in a clash, use a turn to swap places with another card, instantly freeing that card from the clash without forcing it to default to defensive formation. Another lieutenant, the “Necromancer,” could draw reserves from the discard pile. “Rabble Rouser” could, at the start of combat on his flank, use undealt cards from a large deck to deal himself an entirely new random hand, which he would have the option to use instead of his current command. Originally, I had intended for each of the three flanks to be led by a lieutenant and for there to be some sort of morale penalty applied to the flank if the lieutenant was killed, but I never really explored that idea much. Lieutenants are designed to operate a bit differently from normal military cards: they enter the battlefield automatically when the hand begins, they can’t be attacked directly (without a special ability), and their survival doesn’t preclude defeat. I have considered the possibility of allowing lieutenants to fight as ordinary military cards, and I don’t think it’s a bad idea, but I think only those explicitly declared to be commanders — one per flank — should be allowed to use their special abilities.

- Custom Heroes: Almost certainly the most ambitious mechanic I ever imagined for Maraud was a system for players to create their own cards. In the earliest days of the idea, when I fully imagined Maraud as a digital card collection game, I imagined players creating their own custom heroes to lead their armies. I imagined that those heroes would grow and develop using RPG-like mechanics to become more powerful lieutenants and captains. “To the victor go the spoils”: I imagined augmenting cards with items awarded for winning victories. “Defeat builds character”: I imagined new strengths or innate abilities developing as heroes learned from valiant losses. If you defeated another player’s hero, I thought you might get a “snapshot” of that hero that you can use in your own armies. The defeated player wouldn’t lose their card, and your “snapshot” card wouldn’t evolve and grow alongside their character, but the “snapshot” would serve as a unique and collectible memento of your victory. Similar mechanics have been explored in many other genres, so I wondered to what extremes you could push them in a DCCG. But this, of course, is all still purely speculation, for the ideas described here are far beyond anything I’ve attempted with Maraud to date.

This has been one of the most difficult posts for me to write, and I’m honestly not sure why. It’s not because of the length. (It’s partly because of the length.) Perhaps, though, it has more to do with the fact that this game concept is almost two years ingrained in my mind; and from my perspective, I’ve been writing this post backwards. Here, I’ve attempted to explain Maraud from its most simple versions upward, because that’s the pattern I believe will make the most sense to read. However, when I first imagined this game, I approached it from the opposite direction, dreaming wild dreams first and boiling those down to particular mechanics later — or, in some cases, never.

I still regret that I haven’t found a way to push this idea further yet. My original efforts stalled when it became necessary to involve someone with visual art skills to help create better cards than the ones shown above, and I couldn’t find any of my friends with the necessary time, talent, and inclination. But perhaps the friends I mentioned at the start, the ones who requested I do this write-up, will be interested and able to build a fun game from these foundations. Or perhaps you, unknown-other-reader-who-surprisingly-is-still-here-at-the-end-of-this-five-thousand-word-blog-post, will be willing to give it a try. I hope you do. I hope they do. I hope I do. Even when ideas aren’t great or perfect to start with, the more of us who are trying to build on them, the better our chance of creating something fun, right?

-Murray